Student playwrights encourage the voice of the unheard in a student-conceived and -written original production that crackles with youthful insight.

M.P. Hassel

May 3, 2025

In Miz Prophet Tells All, Cassandra’s ancient curse finds new life in the basement of a fractured family, where voices clamor to be heard and truth echoes like static between bodies. Created by student playwrights Yerancy Acevedo, Thaddeus Bey, and Justin Hart, this year’s spring production by Community College of Philadelphia’s Theater Department ran from April 15 through 18 in the Black Box Theater.

The set featured two walls, lined with shelves of paint cans, chairs, and human-sized dolls. A painting on an easel stood mid-stage, eventually repositioned toward the rear as the play progressed. Three television screens played a prerecorded broadcast call and a presidential ad by the cast, while the audience, seated on low-rise platforms, flanked a central alley that doubled as an entrance and, crucially, the basement staircase. The entire room worked in unison to evoke the claustrophobia of Liliana’s world, lending the sense that we, too, were locked down there with her, our only view of escape a staircase through which people descended to enter and ascended to exit the stage.

The play unfolds as a linear series of vignettes, each one tugging us deeper into Liliana’s isolation and defiance. She is grounded to her basement by TV mogul parents for interrupting a broadcast to warn people of her visions of imminent disaster, Liliana is caught in a crisis of credibility, because her warnings are true but ignored by all except her most loyal companions: her playmates.

These playmates – Rose, Stag, and TV Head, among others – are not quite real, but their characters are no less vital. They share Liliana’s basement world, forming a strange, tender conglomerate. Darqui Garcia’s Stag, a mollusk man with a scarf and tweed, offers anxious comic relief and the grounding warmth lacking in Liliana’s tincture, particularly in a moment where he reassures Liliana that “There are no mistakes in painting”—only to quickly revise himself when her attempt to paint hands comes out like stubs: “There are some mistakes.”

Rose, played by Lulu Florea, floats through space like a memory, a flapper in blue. Her quiet sweetness makes a welcome contrast to Liliana’s toppling demeanor. From the writing, the audience can understand their bond to be very close, but the pair lacked the cooperative emotional intensity.

Liliana herself, portrayed by Bethzaida Soto, is a force. Soto imbues every movement with physical urgency. Her Liliana is angry and alert to all collapse, hypocrisy, and tragedy. She wants to be an artist but cannot yet paint hands convincingly. Stag encourages her, and Hector later jokes that paws would be easier. This thread of artistic incompletion becomes symbolic of her struggle to be understood, to reach out.

TV Head, portrayed by Peter Chen, was a particular delight, flickering between the nervous sidekick and audiovisual guide, the lines were prone to be delivered too quickly. Physically, he gave the character a light energy, dancing immediately upon entry and always dynamic. With technology on his head and a computerized cadence akin to BMO in Adventure Time, he oriented the audience to the screens above for a video or centerstage for a broadcast vignette from news anchor Marina and rockstar weathergirl Miss Magenta, played by Melek Ercan and Mikayla Matthews.

Later, Mazi, played by Mody Diakite, joins the campaign against Liliana’s parents. His presence charges the air with anxious energy, disrupting the rhythm just enough to spark transformation, or at least the possibility of it. These playmates are extensions of Liliana’s psyche, or projections of her longing for voices that see her, challenge her, and believe her.

Her family, played with sharp contrast by the supporting cast, defines itself through greed. Sol, her father, is played with cold authority by Jarrell Brooks-Lyons, who leans into a conniving posture with a downward gaze, to diminish Liliana in every encounter. In a play about power and perception, this unintentional visual irony could not have been pushed further to subvert the script’s hierarchical tension lest he act the patriarch with chin high with pride. Phoebe, Liliana’s mother, is performed by Esther Pavlov with theatrical flair. Her character’s break comes not with her daughter, but with her husband, Sol, on a vignetted broadcast apology for her Liliana’s behavior. In a moment of shrieking hysteria that teeters into comedy, Sol shrugs her embrace to conclude the broadcast and land the punchline. It borders on the comedic, yet Pavlov balances it with a simmering distaste for her daughter that feels all too real. Orayuan Gonzalez, as Troy, the self-styled “President Business,” leans into his character’s performative bravado. His confidence in monologue is undeniable, though his quieter moments strain under the weight of sincerity. Still, his stage presence and control suggest incredible potential.

Then there is the dog, Hector, played by Trung Cung, who is truly the only one of her family in her corner, but perhaps the most overtly comedic role. His embodiment of a spaniel has full carnival face art, floppy dog ears, and a wryly British accent. At one point, he barks at Liliana with such conviction that the audience flinched like a collective mail courier and returned to laugh in the same breath. But beyond the laughs, Hector sits at the edge of the real world, entering and exiting at the top of the staircase, the play’s most imaginative piece of stagecraft, where the light suggests an open door. His presence there makes him a kind of sentinel, beckoning Liliana toward release, or reintegration, or some upward motion.

The family members use that staircase too. Sol, in particular, after he is done circling and mocking Liliana ascends the alley and off-stage treats, but calls back to Hector like a pet, then mocking him with commands like “want walkies?” The staircase frames the play’s fundamental question as ‘who climbs, and who remains below?

Technically, the play makes effective use of lighting and repetition. The broadcasts Liliana sees are projected on the screens or acted live centerstage in focused lighting but still across the basement backdrop. News, memories, and visions all happen in the same confined space. This visual choice reinforces the idea that her entire world is filtered through her confinement. The repetition, particularly when her family circles her reciting lines from earlier on under strobe lights, achieves a chilling effect, like sharks encircling her in dark water. That moment nearly collapsed under wobbly timing in the overlap of lines but recovered quickly.

If the play falters, it’s in pacing. Some repetitions run too long. At one point, characters belabor the naming of her livestream – “Miz Prophet Tells All” – as if arriving at an epiphany the audience reached much earlier. Literary allusions come thick and fast, sometimes to the point of drowning the emotional core of the scene. In these moments of rapid dialogue, the script wants to be urgent and layered, but the lines suffocate emotional clarity within their natural cadence.

Still, Miz Prophet Tells All dares to ask what prophecy looks like not from Mount Olympus, the pulpit, or official office, but from a basement, where a girl with visions of hurricane winds and highway pileups tries to reach the surface. In the end, she doesn’t climb the stairs. With her family scattered off on Election Day to Venezuela, her presidential candidate brother reportedly a felon, Liliana stays below. She says goodbye to her playmates as they entreat her to push on. She paints perfect pink hands on the canvas and walks toward the audience, palms up.

It is a gesture of both surrender and self-assuredness. Liliana claims the basement as Soto claimed the stage as Acevado, Bey, and Hart claimed the script. Her voice may not be welcomed or celebrated above, but it resonates here. The light at the top of the stairs glows warmly, but still indifferent. Hope lives in the persistence of voice, not in escape, but in echo.

Post-script: Behind the Vision

Miz Prophet Tells All was born from a year-long process rooted in devised theater, an approach that builds performance through ensemble collaboration rather than a single author. Theater instructor Jonathan Pappas began developing the idea during a 2023 sabbatical focused on this method, ultimately blending it into his coursework across the academic year. Students from his Fall 2023 Playwriting and Acting I classes initiated the conceptual groundwork, which grew into a collaborative writer’s room in Spring 2024, where the final script was shaped by Yerancy Acevedo, Thaddeus Bey, and Justin Hart.

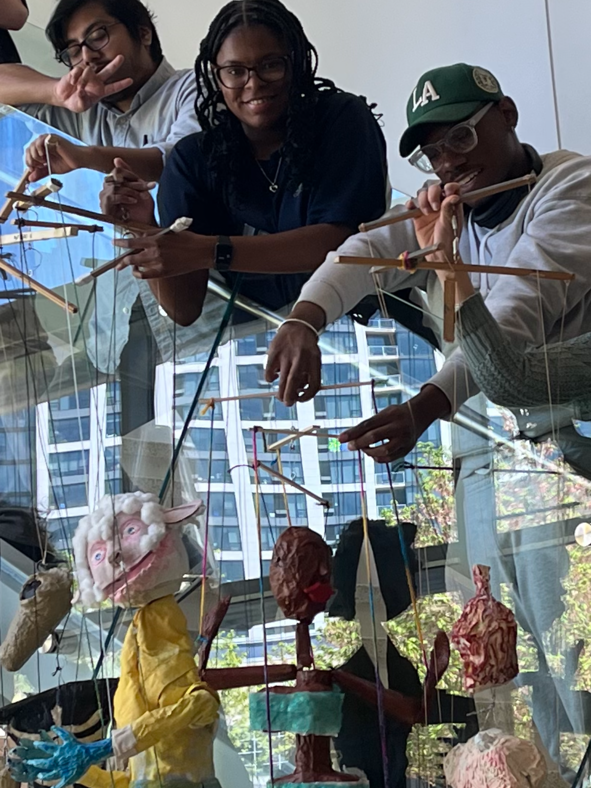

The production drew further support from students in Pappas’ Technical Theater course, who built set pieces and puppets, and Quinn Eli’s Acting II students, who joined the cast. As Pappas put it, “We set out to prove that a student-led production doesn’t have to look like a student-led production.”

To better understand the story’s core, The Independent corresponded with writer and co-creator Justin Hart about the play’s themes and process.

Q: What was the brainstorming and writing process like for Miz Prophet Tells All?

The brainstorming process for Miz Prophet Tells All, was very loaded. We knew very early that the school wanted the play to basically be a modern retelling of the myth of Cassandra, except she had to be locked in the basement, and she had to have puppets. So the writers and I, along with a few other contributors, took September to November to really create and develop the characters and plot out the story. The quotes and references were first brought in because we knew we wanted one of the puppets, named Stag, to be philosophical and refer to a lot of quotes, but we also wanted the story to connect with the audience.

Q: Were there particular themes you were most passionate about getting across?

I think the biggest concept that I really want to stress was the very visible connection between politics and media, and their influence over the general public. Along with the importance of having somebody who’s not afraid to be able to stand up to tell the truth, even if they get ridiculed. Lastly, we really wanted to highlight the hardships that women may face of trying to have their voice heard, and that sometimes it’s not a easy thing to do, however, it is not impossible.

Q: What’s something about the play that you wish the audience knew?

The only general thing that I can say I wish the audience could know about the play is that the parents take the role of Apollo from the Greek myth of Cassandra, and not Cassandra’s actual parents.

Thank you to Prof. Jonathan Pappas and Quinn Eli for photos of the play.

Leave a comment